|

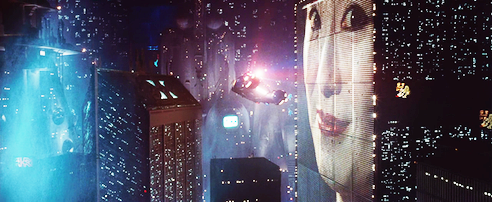

| Blade Runner, dir. Ridley Scott (1982) |

The films we discuss on this blog are often an individual

view of the philosophy in [insert title here]. But we also have public

discussions - Philosophers at the Cinema is a regular season of screenings at

Norwich's delightful Cinema City. Recently, collective members Vincent M. Gaine

and Rupert Read went on Radio Norfolk to discuss this programme and our latest

showing, Blade Runner. The screening was followed by a discussion around the

philosophical points of the film, which included such points as the environmental damage depicted in the film, and the importance of animals in relation to empathy and the loss thereof.

Blade Runner is a film that prompts a plethora of

interpretations and debates, the least interesting of which is "Deckard -

replicant or not?" Of particular interest to me is the film's future world

(now only three years away), in which technology, capitalism, consumerism and advertising

has completely taken over. It is testament to the film that its Los Angeles

expresses so much through suggestion and implication, not explicating why large

buildings are deserted, why it rains so much, what happened to all the animals.

Omnipresent advertising bombards the inhabitants of this city at every turn,

promoting "A better life" that seems perpetually out of reach.

|

| Blade Runner, dir. Scott (1982) |

It is unsurprising that replicants - artificial people -

have become indistinguishable from humans in a world where artifice is so predominant.

A key philosophical question, as discussed by Locke and Dennet, is what

constitutes a person. While one can ask these questions about the replicants,

it seems appropriate to ask them of the (presumably) human characters as well,

not only Deckard but also Bryant, Sebastian, Tyrell and Gaff. If a key element

of being a human/person is empathy, Bryant and Gaff at least are largely

impersonal. Bryant refers to replicants as "skin jobs," while Gaff

regards Deckard's work of licensed executioner as "a man's job."

Tyrell is far from empathetic, indeed his intellect seems to have divorced him

from emotion. His creation and then rejection of Rachael is irredeemably cruel

- he created an entity that can think and feel, then discards her when she

becomes inconvenient. Roy fares no better - his brief lifetime little more than

an academic discussion for Tyrell. Tyrell's death is therefore fitting, his

head crushed by Roy while (in the Director's Cut) the viewer sees the impassive

and unconcerned owl. Much as Tyrell has no concern for the replicants, this

artificial bird has no concern for him. By implication, nor does the film or

its world. Personhood is deemed insignificant by the omnipresence of consumer

technology, the agony of Tyrell evincing as much sympathy as the swift

retirement of Leon. Blade Runner therefore performs philosophy through its

prioritisation of commerce over humanity, as salient a message today as when

the film was first released.

| Blade Runner, dir. Scott (1982) |